Blitz Bureau

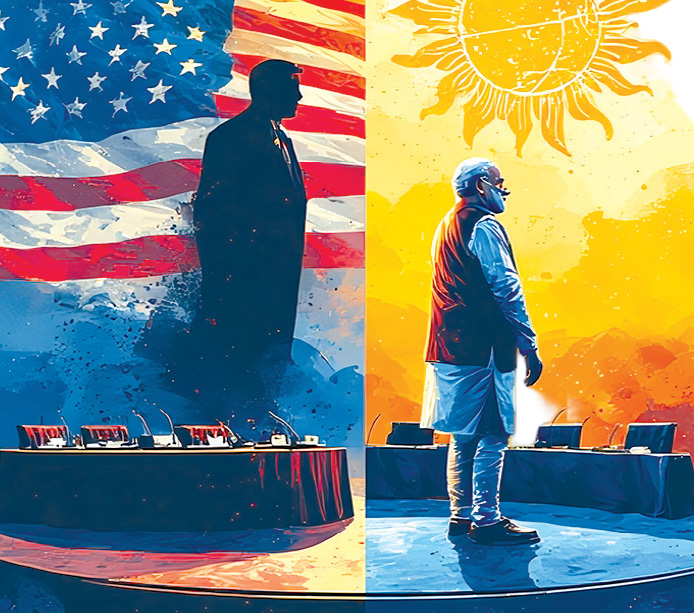

NEW DELHI: President Donald Trump’s reported decision to pull the United States out of 66 international organisations — including the India-led International Solar Alliance (ISA) — has been projected as a dramatic rupture in global climate diplomacy.

In reality, its deeper significance lies elsewhere. This is less a story about America’s withdrawal and more a test of India’s readiness to lead without Washington’s shadow —or approval.

For New Delhi, the US exit is not merely a diplomatic setback. It is a stress test of whether multilateral institutions led by emerging powers can endure, and even thrive, when Western political support ebbs. As a country that increasingly positions itself as the voice of the Global South, India now faces a defining moment: Can it convert convening power into durable leadership?

The Trump administration’s move reflects a sharp return to transactional, sovereignty-first diplomacy. Climate institutions that hinge on shared obligations, concessional finance and technology transfer sit uneasily with this worldview.

From Washington’s perspective, such platforms constrain autonomy while offering uncertain returns. That logic may explain the exit — but it does not invalidate the ISA’s raison d’être.

Crucially, the ISA was never conceived as a US-centric platform. Launched jointly by India and France, it sought to fill a long-neglected gap in global climate governance: affordable solar deployment for tropical and developing countries. Its focus was implementation, not norm-setting; delivery, not declarations. America’s departure weakens symbolism, but it does not dismantle the alliance’s core logic.

India now has a choice. It can treat the US exit defensively, as a diplomatic loss. Or it can seize this moment to assert a more confident form of leadership — one that does not depend on Western participation to validate its relevance.

Admittedly, the absence of the world’s largest economy and a major technology innovator will be felt. Research collaboration, concessional finance leverage and political heft all take a hit. Yet in practical terms, US involvement in the ISA’s day-to-day functioning was limited.

Strategically, the opportunity is significant. With over 125 member countries, the ISA can now recast itself explicitly as a Global South–first institution, focused on deployment, affordability and climate resilience rather than rules shaped by advanced economies.

If India succeeds, the ISA could become a template for issue-based coalitions where leadership is earned through delivery, not dominance.

For India, America’s exit from the solar alliance is not merely a diplomatic setback. It is a stress test of whether multilateral institutions led by emerging powers can endure, and even thrive, when Western political support ebbs.

The broader concern is global fragmentation. Without US participation, climate finance could become more regional, standards more uneven and coordination harder. This raises the premium on India’s coalition-building skills — with the EU, Japan, the Gulf states and other emerging economies — to keep momentum intact.

At home, India is better prepared than ever. Its own energy transition — balancing growth, affordability and decarbonisation — is already under way. Rapid solar expansion, green hydrogen ambitions, grid-scale storage and domestic manufacturing form the backbone of its climate strategy.

The ISA is a natural extension of this approach, converting domestic capability into diplomatic influence.

Ultimately, the US exit shifts the spotlight squarely onto India. The question is no longer whether Washington supports India-led climate platforms, but whether India can sustain them through credibility, financing innovation and institutional delivery.