Blitz Bureau

NEW DELHI: Pakistan’s $500 million rare earth pact with US Strategic Metals has been hailed by Islamabad as a landmark deal — a gateway to modernisation, foreign investment, and entry into the global high-tech value chain.

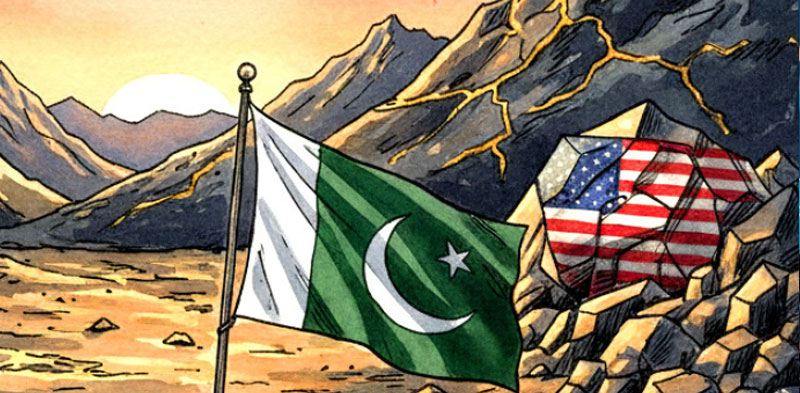

Yet, behind the glitter of critical minerals lies a more sobering question: Is Pakistan gaining strategic leverage or merely exchanging one dependency for another? The stakes are immense, touching not just economic prospects but national autonomy in an era where control over critical resources defines geopolitical relevance and technological sovereignty.

Its recent tie-up with US will end up in servitude and force it away from China

Rare earth elements (REEs) — vital for electric vehicles, semiconductors, and defence technologies — are the new oil of the digital era. With China dominating 70 per cent of global production and 85 per cent of processing, the West is desperate to diversify supply chains.

Pakistan’s reserves, spread across Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan, offer Washington an alternative foothold in South Asia. But for Islamabad, the challenge is deeper: how to convert resource wealth into sovereign strength rather than strategic servitude.

The deal promises capital, technology transfer, and local jobs, but its structure raises concerns. US firms are expected to control extraction, refining, and export channels, with Pakistan primarily supplying raw ore.

Without domestic value addition, Pakistan risks replaying its old script — exporting raw materials while importing finished products at far higher costs. Such extractive models have historically trapped nations in low-income cycles, eroding fiscal autonomy and industrial depth.

Moreover, the geopolitical undertone cannot be ignored. As Washington builds a “critical minerals alliance” to counter Beijing, Islamabad may find itself pressured to choose sides in a rivalry it can ill afford. The US investment, though welcome, could entrench economic and diplomatic dependencies, limiting Pakistan’s freedom to balance ties with China, its largest trading partner and a key investor in mining infrastructure under CPEC.

For India, the episode offers important lessons. New Delhi has adopted a more calibrated strategy — identifying 30 critical minerals, opening domestic exploration to private players, and investing in downstream processing.

Rather than signing resource-for-cash deals, India is building capacity across the value chain, from mining to refining and advanced manufacturing. This ensures strategic autonomy while integrating into global supply networks on more equitable terms.

India’s policy mix — Production Linked Incentives (PLI), strategic partnerships in Australia and Africa, and the Critical Minerals Mission — seeks to balance openness with sovereignty. The focus is on technology acquisition, domestic beneficiation, and diversification of supply sources, avoiding overreliance on any single bloc.

Pakistan’s gamble, by contrast, exposes the perils of short-term fixes in a long-term game. Without strong regulatory frameworks, transparent contracts, and reinvestment in local industry, resource deals risk becoming modern concessions rather than instruments of empowerment.

In the geopolitics of critical minerals, ownership matters as much as access. Nations that merely extract remain vulnerable; those that process and innovate command the real power.

Pakistan’s rare earth venture could either mark the start of industrial renewal — or another chapter in resource dependency. The difference will lie in whether Islamabad uses this opportunity to build capabilities, or sells its future for upfront cash.